Even if it was created by an artist or charlatan several hundred years ago, as of yet there has been no explanation how such an ingenious rendering could have been created with the technologies of the day.īut maybe so much focus on explanation misses the point.

This is not to say the puzzle has been solved. Twelve hundred years too young, the Shroud is most likely a medieval creation. Undertaking separate studies using accelerator mass spectrometry in the laboratories of the University of Arizona, the University of Zurich and Oxford, these studies found, with 95% certainty, that the fabrication date of the linen of the Shroud was sometime between 12. In 1988, groups of scientists from three countries were allowed to perform radiocarbon dating on fibers from the Shroud. According to the most recent research, at the time when the Templar initiate claims to have seen it, the Shroud now housed in Turin probably didn’t exist. Frale and others who have seized on the story is a slight complication. It was the Shroud, and it was the Templars who brought it from Constantinople to French Diocese of Troyes, where it would soon be “discovered” before being moved to Turin.Īpparently ignored by Dr. She writes of a young French Templar, Arnaut Sabbatier, who joined the order in 1297 after undertaking a ritual in which he was instructed to kiss “a long linen cloth on which was impressed the figure of a man.” This cloth, Dr. Frale’s document may explain such allegations. According to the text (uncovered by Vatican researcher Barbara Frale), until 1354 the Shroud was safeguarded by the Knights Templar, a military order that was popular and well supported within the Church, even if they were occasionally accused of idolatry and sodomy.ĭr. The recently discovered document puts the Shroud briefly in the hands of a controversial band of crusading knights. To wade into the murky waters surrounding the Shroud and its history is immediately to contend with conspiracy theories both grand and mundane. Showing as it does that universal, unavoidable image-a man, naked, prepared for the grave-the Shroud serves as a reminder that the stories of religion are first of all stories of human lives. Such statements remind us that it is the very physicality of these relics that makes them important to believers this same factor may make them meaningful to nonbelievers as well. “The Shroud is not Christ, but a reminder of him,” Cardinal Giovanni Saldarini, former Archbishop of Turin, has said. Inevitably, the light of this renewed interest shone just as brightly on longstanding doubts. With the announced discovery of a document explaining the 150 years in which the Shroud disappears from the historical record, Vatican researchers attempted to provide a missing link that could bolster claims of authenticity. To know who he is, and why he matters, we need to ask how he got there.Ī partial answer came around this time last year, when a report from Rome shined new light on Christianity’s most hotly-contested stretch of cloth. Like any good true-crime story, the mystery of the Shroud starts with a body. Given the dubious provenance of such artifacts (my clear dismissal of the possibility that the Shroud is what believers claim has apparently been left on the cutting-room floor), I hoped to make the case that the most interesting question to ask of them has little to do with authenticity: Why should physical objects hold such enduring spiritual fascination? In general, it is not the fact of relics that matter, but the stories behind them. My main purpose in the film was to explain that the Shroud is one of the objects related to the events Christians commemorate this past weekend, including the Spear of Destiny (said to be the Roman soldier’s lance that pierced Jesus’ side), the Crown of Thorns, a handful of Holy Nails, and a Holy Sponge (from which Jesus drank gall before he died).

#PICTURE OF JESUS SHROUD OF TURIN SKIN#

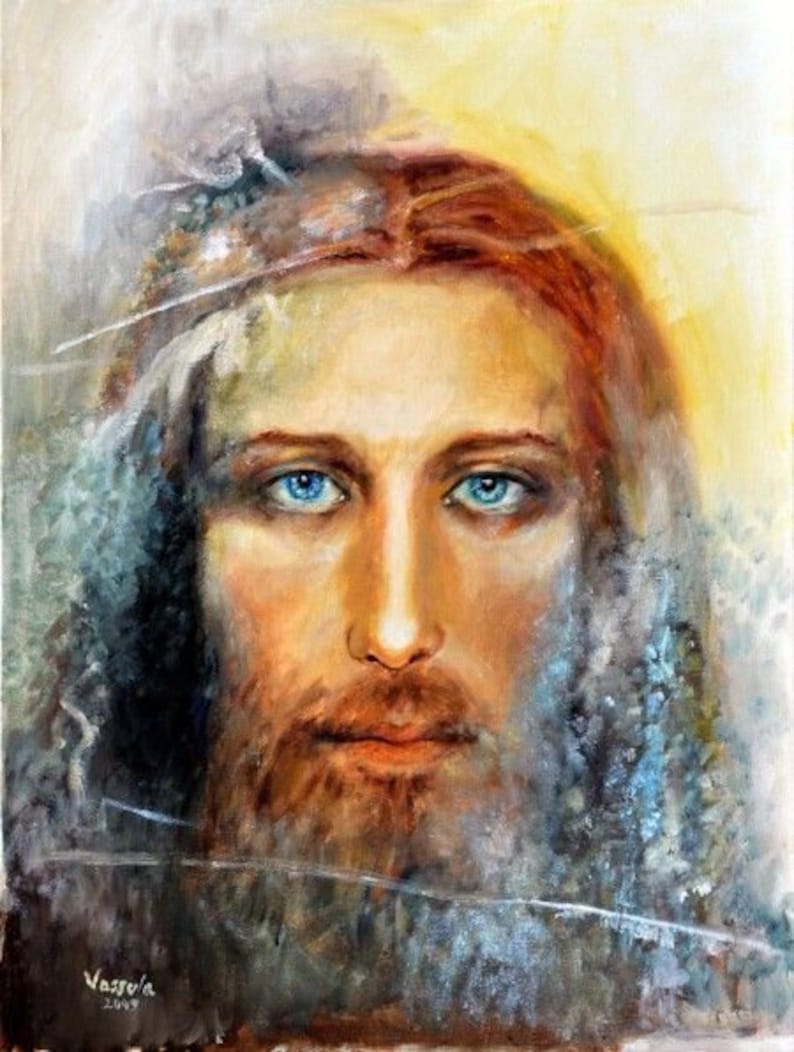

The lastest cops on the beat are the makers of a new documentary for the History Channel, which purports to reveal “ T he Real Face of Jesus” through three-dimensional imaging and CGI graphics that make the viewer wonder if Christ might be revealed to have blue skin and a Nav’i tail.īecause I have written about religious relics, I was brought in to serve as a talking head on the documentary. Since that fateful photoshoot, Pia’s snapshots-the first of the religious artifact known as the Shroud of Turin, the supposed burial cloth of Jesus Christ-have been reproduced around the world, turning up every few years like crime scene photos from the coldest of cases.

Just over a century ago, when Turinese photogtrapher Secondo Pia received permission to create glass-plate renderings of a tattered piece of cloth in a local church, he had no idea that his camera would capture images fit for both scripture and film noir.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)